Introduction

Central Asia remains one of the world’s youngest regions, demographically, politically, and institutionally. This also holds true for the think tank sector, where the culture of independent policy research is still in its infancy. Many local think tank professionals agree that it is too early to describe the sector as fully developed or mature. Instead, what we see is an early-stage momentum: countries in Central Asia are beginning to open their eyes to the possibilities of using rigorous research and evidence-based ideas to inform their policy debates and development trajectories.

The think tank map across Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan still looks sparse, resembling a night sky with few visible stars. + Yet, these faint points of light are steadily multiplying, pointing to the new wave of think tanks that could shape policy dialogue and decision-making in a time of rapid social, political, and economic transformation.

This period is crucial for both observers and practitioners. It presents a unique opportunity to track where, how, and which ideas are emerging, gaining traction, or fading away, and ultimately, which ones influence governance and policymaking in the region.

This brief report, developed through a regional partnership between CAPS Unlock and On Think Tanks as part of the 2025 State of the Sector Report, provides a snapshot of the think tank sector across the four Central Asian countries.

Download the On Think Tanks State of the Sector Report 2025

By widening its scope and attracting more regional participants, this year’s survey offers a sharper view of the sector’s varied organisational types, operational models, and thematic priorities. Drawing on the voices and perspectives of local think tanks, the report examines the realities they face, ranging from internal capacities and financial conditions to the broader political environments that shape their independence and influence.

The report reflects the firsthand perspectives of think tank professionals, highlighting both significant progress and persistent challenges across key areas such as organisational structure, funding, core activities, target audiences, impact, and operational difficulties. It identifies how the sector assesses its influence and identifies priorities essential for fostering growth and ensuring long-term sustainability.

Beyond providing insights for donors, international partners, and policymakers, this report functions as a valuable self-assessment tool for the Central Asian think tank community itself. Developing a robust, independent, and impactful policy research sector is vital not only for enhancing decision-making processes but also for promoting transparency, accountability, and sustainable development.

Methodology

This report is based on a survey of 20 think tanks operating across Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan. The sample comprises a range of institutions that vary in size, legal status, and thematic focus, reflecting the sector’s growing diversity. The survey covers aspects such as organisational structure, funding environment, research independence, and sector challenges. Further methodological details will be shared by our partner, On Think Tanks.

This report intends to provide a foundational understanding of Central Asia’s think tank sector today and to set the stage for ongoing dialogue, collaboration, and support as the ecosystem continues to evolve.

Snapshot: Think tanks in Central Asia

The think tank landscape in Central Asia has developed in two clear waves. The first, emerging after the collapse of the Soviet Union, was dominated by state-affiliated institutions embedded in government structures, functioning primarily as internal advisory bodies with limited public engagement. The second wave, more accurately reflected in this survey, is younger, more diverse, and largely independent of the state.

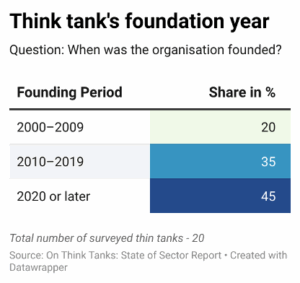

All 20 organisations surveyed were founded after 2000. Nearly half of those appeared within the last five years. Many newer institutions were created by civic leaders, academic networks, or through international partnerships, demonstrating a gradual but steady growth of non-state-affiliated policy research in the region.

Legally, the majority are registered as non-profits (65%). Another 25% operate as university-based research institutes. Only one organization is a government entity, and another a private consultancy, indicating that the survey captures primarily publicly oriented institutions rather than commercial or opaque state-linked actors.

Geographically, most operate at the national level (85%), though more than half (55%) also work across Central Asia. A small number extend their activities to community-level or global audiences.

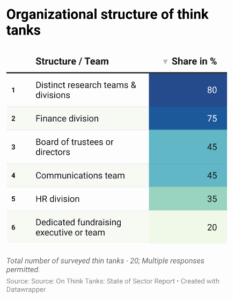

Structurally, these think tanks remain lean but relatively well organised: four out of five have dedicated research teams, and three-quarters maintain finance divisions. But less than half have formal boards or dedicated communications units, and only a minority have HR departments (35%) or fundraising specialists (20%). This points to a reasonably solid internal backbone, but underdeveloped capacities in governance, outreach, and resource mobilisation are also notable features.

Leadership tends to come from academia (40%) or the public sector (25%), with fewer directors from civil society (20%) or business and politics. While men still lead a majority of think tanks (55%), a notable 20% report co-leadership models with both male and female executives.

Workforces are small. Three organisations have no full-time employees, and most employ fewer than 20 people. Nevertheless, every organisation has at least one PhD-level researcher, and one-third report that the majority of their staff are under 35, reflecting an emerging generation of policy professionals. Only 25% offer long-term contracts to most of their employees, revealing ongoing challenges in securing stable talent and ensuring institutional continuity.

Core activities, audiences & impact

Think tanks in Central Asia, much like their counterparts worldwide, operate around two core functions: producing research and engaging audiences. Nearly all surveyed organisations publish policy briefs and analytical reports, while a substantial majority also host events (lectures, conferences, and expert workshops) to share findings and encourage debate (about 75%). Extending their reach, most maintain a presence in both traditional and digital media (70%), and many go further by providing tailored policy advice to governments and other stakeholders (60%).

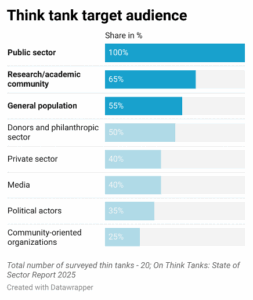

The public sector remains the primary audience for all think tanks, though access to key decision-makers is not always guaranteed. To broaden their influence, many cultivate relationships with universities and academic networks (65%) and target the general population (55%). Donor engagement also features prominently, with half of think tanks maintaining links to philanthropic or development organisations. Engagement with the private sector (40%), media professionals (40%), or political actors (35%) is less consistent.

Research agendas are shaped primarily by the demands of public policy (85%), followed by political developments (70%) and funding opportunities (70%).

According to respondents, government institutions and policymakers hold the strongest influence over research and policy priorities, with international organisations following closely. Academic institutions and other think tanks play a secondary role, while civil society, media, the private sector, and social media exert comparatively limited sway. If think tankers could set the agenda themselves, they would concentrate on five main themes: economics, education, law and human rights, governance, and the environment.

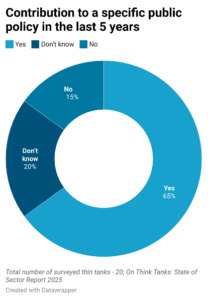

On the question of impact, Central Asian think tanks express cautious optimism. Around two-thirds (65%) believe their work has informed or shaped public policy in the past five years.

Approaches to measuring this influence vary: some track evidence of policy uptake or citations (45%), while others view the diversity of their funding base as a marker of success (35%). Smaller proportions rely on media coverage (15%) or social media metrics (5%).

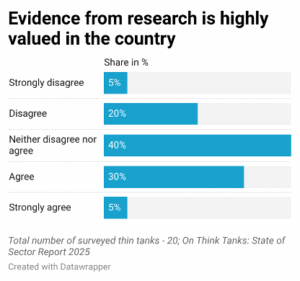

Despite this relatively positive view of their policy influence, many remain unconvinced about the broader culture of evidence in policymaking. Only about a third (35%) agree that research is highly valued in their national context, while nearly half are either sceptical or neutral. This ambivalence is mirrored in their outlook for the sector itself—just 40% expect growth in the coming year, compared to half who foresee no significant change.

Funding

Funding for think tanks across Central Asia remains largely project-based, with over half of the surveyed organisations (55%) relying primarily on project-specific grants. Only around 20% of organisations benefit from core funding that supports essential operational costs, such as salaries, rent, and administration. This gap poses challenges to financial stability and operational flexibility.

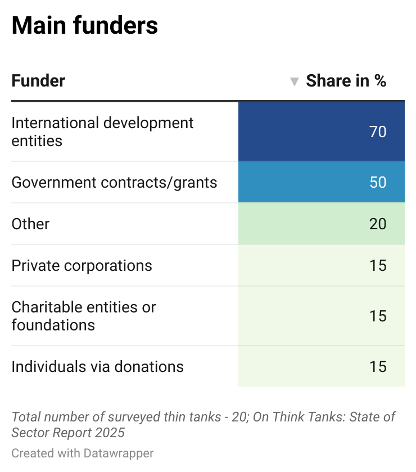

Grant durations tend to be short, with about 60% lasting one year or less, making long-term planning difficult. The main sources of funding are international development agencies (70%) and government contracts or grants (50%). Consulting projects and project-specific grants dominate, while core or programmatic funding is less common. Revenue from membership fees or service sales is minimal.

Covering indirect costs — i.e., administrative overhead and facilities — is a persistent struggle. Nearly half of the surveyed organisations report difficulties in financing these expenses, with indirect cost rates typically ranging between 10% and 50% of direct project costs. This highlights the limited capacity to support overheads from grants.

Recent financial trends reveal a mixed picture: approximately 35% of think tanks reported funding increases over the past year, while 30% experienced cuts, and another 35% reported little change. This volatility shapes current responses —many organisations have reduced operating costs and sought new partnerships. Still, widespread staff reductions or aggressive funding diversification are rare, partly due to already small teams and a tight funding landscape. Notably, the withdrawal of USAID support has not significantly impacted most respondents.

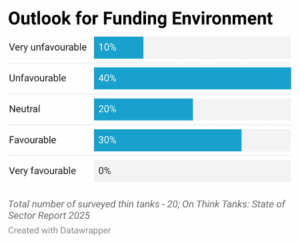

Looking ahead, perceptions remain cautious. Half of respondents (50%) anticipate a worsening funding climate over the next 12 months, while 30% hold a more optimistic view, and the remainder expect no significant changes. Despite this, a majority (55%) plan to expand, aiming to strengthen research capacities and deepen international collaborations. Many intend to recruit in research, technology, and communications, even as they prepare for constrained resources.

Fundraising efforts are generally modest, with only 35% reporting significant or extensive fundraising activities (20% significant, 15% extensive), while the majority (65%) dedicate minimal to moderate effort. The sector thus faces a delicate balance, pursuing growth and opportunity where possible, but largely relying on careful cost management and selective partnerships to navigate ongoing uncertainty.

Challenges

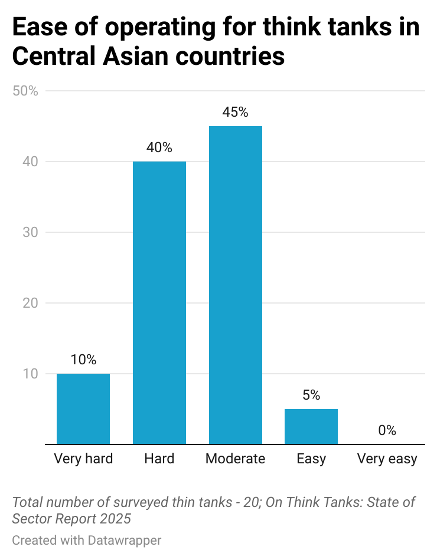

The operating environment for think tanks in Central Asian countries remains demanding, though experiences vary between the sector as a whole and individual organisations. At the sector level, half of the respondents describe conditions as hard or very hard (50%), with nearly as many finding them moderately challenging (45%) and only a small minority considering them easy (5%).

When reflecting on their own organisation’s experience over the past year, more respondents rate conditions as moderate (55%), fewer report significant difficulties (35%), and a handful find operations relatively smooth (10%). This suggests that while structural barriers are broadly felt, some think tanks are better equipped to manage them.

Human capital and resource constraints consistently emerge as significant challenges. A majority (65%) highlight a shortage of skilled professionals, which limits their capacity to conduct and sustain quality research. Securing new funding sources is perceived as an even greater hurdle, with 70% reporting this as a pressing issue. Staff turnover also disrupts continuity for over half of organisations (55%), and leadership transitions, while less frequent, still pose difficulties for 35%.

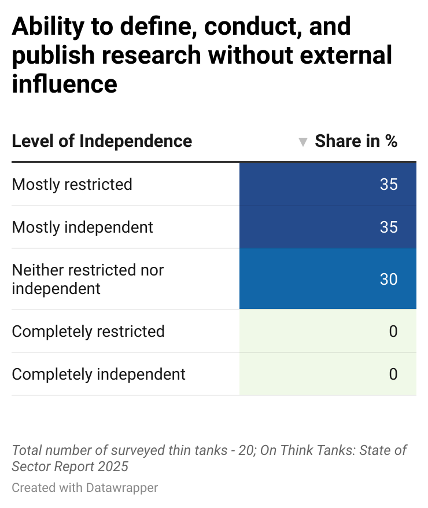

Regarding research independence, the sector occupies a middle ground. An equal share feels independent primarily (35%) or mostly restricted (35%), while the remaining 30% report a neutral balance between autonomy and external influence.

The political climate over the past 12 months has had a mixed impact. For many, conditions were neither clearly positive nor negative (45%), though a notable minority experienced unfavourable circumstances (30%), and some found opportunities (25%). As for the future, opinions remain split: 30% expect a more supportive political environment, another 30% anticipate increased challenges, and 40% foresee relative stability.

Political polarisation affects most think tanks to some degree, with 70% reporting at least a moderate impact on their ability to operate effectively. For a quarter of respondents, polarisation complicates how they share research and engage with diverse audiences. The same share sees it as hindering collaboration with policy experts across the political spectrum, limiting cross-partisan dialogue. A smaller portion (20%) believes polarisation restricts their ability to attract funding from diverse sources, potentially narrowing financial options. Only 5% report reduced media access as a direct consequence, indicating that while visibility challenges exist, they remain limited for now.

Conclusion

Central Asia’s think tank sector is young but growing quickly. These organisations are driven by a clear mission: to produce independent research that can inform better policies and public debate. Yet, they face significant hurdles. Funding is often unstable and tied to short-term projects, making it hard to plan ahead or invest in long-term development. Many struggle with limited staff and a shortage of skilled experts. Political pressures and limited access to key decision-makers add further challenges.

Despite these difficulties, the sector shows signs of determination and gradual progress. Think tanks are expanding their research activities and working to increase their influence both domestically and internationally. Many are stepping up efforts to engage with government officials, donors, academia, and civil society, aiming to broaden their reach and relevance. They recognise the need to build stronger internal systems, such as governance, communications, and fundraising, to support this growth.

This report captures the current state of the sector: its strengths, weaknesses, and priorities. It reveals a group of institutions balancing ambition with caution, aware of their important role but constrained by external and internal factors.

For donors, policymakers, and partners, this report highlights where support is most needed, whether it be longer-term funding, capacity building, or fostering connections with decision-makers. For think tanks themselves, it offers a clear picture of shared challenges and opportunities, encouraging reflection and collaboration.

In short, the Central Asian think tank sector stands at a critical point. The next few years will be decisive in shaping its future. The right investments and strategies could turn emerging potential into lasting influence, helping these organisations play a stronger role in shaping the region’s policies and development paths.